What is the power of a memorial?

In Montgomery, the Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice has single-handedly made the nation confront its violent racial past.

Until its debut in 2018, mentioning racial violence like lynching was still taboo. Some museums made reference, but for the most part it was too much to put front and center.

The “Lynching Museum” or “Lynching Memorial” as its often called, has changed all that. Across the country, cities from Charlottesville, Virginia, to Abbeville, South Carolina, have taken note of their violent history.

The Montgomery civil rights museum and memorial takes visitors on a gut-wrenching journey through some of America’s darkest moments. It has been called the most important U.S. memorial since the debut of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on Washington, D.C.’s National Mall in 1982.

For many, a visit is the emotional climax of a civil rights tour, a memory that stays with them for a lifetime.

Montgomery’s museum complex was created by attorney Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, which works to free falsely convicted death-row prisoners. Many know of him through his book and film, Just Mercy. The six-acre outdoor memorial looms on a hill above downtown Montgomery, and includes an adjacent restaurant, exhibit area and shuttle stop.

It’s located about a mile from the museum. And while the expanded museum and its unflinching look at slavery may be upsetting to some visitors, it’s the monument that staggers.

To start your visit, head to the museum, where you’ll find free parking, the ticket office, and a gift shop.

Shuttle buses often operate between the museum and memorial, but if the weather’s nice, it’s an easy 20-minute walk. (However, in the heat of summer, the shuttle is a welcome amenity.)

| If you’re traveling to Atlanta, and eager to see Alabama’s most important civil rights sites, you can experience them all in a day on a unique package tour. A marathon 12-hour tour with a driver/guide visits the landmarks in Birmingham, Selma, Montgomery and Tuskegee, including a stop at the lynching memorial. |

Start at the Legacy Museum

You’ll want to begin at the Legacy Museum, 400 N. Court St., which serves as a visitors center for the Equal Justice Initiative complex, and is home to a thorough, compelling and haunting museum. Click to jump ahead to the Memorial.

While the Memorial specifically focuses on lynching and racial terror, the Equal Justice Initiative provides context at the Legacy Museum.

The 40,000 square-foot building, which opened in 2021 three years after the Memorial’s dedication, takes a long look at the country’s history of slavery and racial oppression. Set out like a carefully structured legal argument, it systematically shows how slavery led to segregation during the first half of the 20th century, and how that led to what now is the mass incarceration of Black men.

Using digital projections and other immersive exhibits, the museum makes a powerful argument. It will leave many visitors questioning their assumptions and seeing the world in a different context. Knowing that the building’s located on the former site of a cotton warehouse where enslaved workers were held in pens and forced to labor only underscores the point.

It short, it’s a must-see museum. But a word of warning: The subject and presentation may be too intense for some children.

Visitors start with a long haunting walk down a dark hall, where a tall video of towering waves overwhelm bodies at the bottom of the ocean and threaten to engulf us. It’s our introduction to the harrowing Middle Passage and the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Projected words note that 12.7 million captured Africans were kidnapped and transported to the New World by, and 2 million of them died during their relocation. One woman pleads for her child, who has been taken from her, and begs you to help. Oscar-winning actor Lupita Nyong’o tells how slave ships carried human cargo

Holographic figures call out from cells on the side. Even though it’s an electronic projection, the plea cuts to the heart, and it’s hard to walk away.

With that introduction, the museum slowly and carefully makes its argument, exploring the economics and horrors of slavery. It describes how families were routinely broken up, women raped and the enslaved menaced.

Enslaving people was big business, with direct ties to the financial sector. Banks accepted slaves as collateral for loans. And cities like Boston; New York; Providence, Rhode Island; and New Haven, Connecticut, all had deep financial ties to the slave trade, it notes.

Following Emancipation slavery simply evolved. Jim Crow laws codified segregation, and lynching assured that white supremacy continued. Take time here to get context for the Memorial. You’ll see how anything could provoke a lynching, from failing to address a white man as “Mister” to telling children to behave.

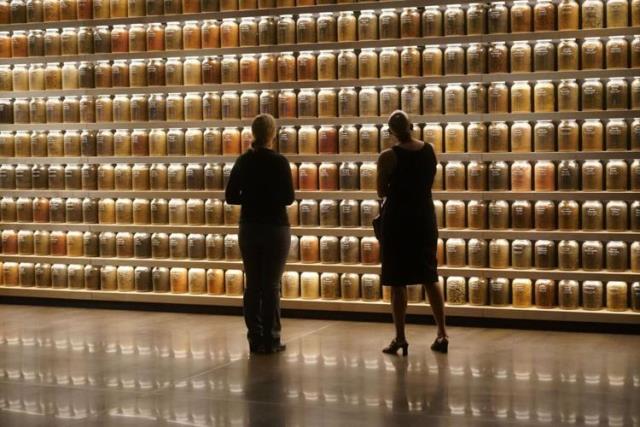

Lynching, exhibits note, was an accepted part of life, covered in newspapers, and at times public entertainment. One of the most powerful wings of the museum displays 800 large backlit jars. Each is labelled with a name, a location and a date, and filled with soil taken from the site of a documented lynching,

Then as the civil rights movement began to reap benefits, the newest form of repression became incarceration. Bryan Stevenson made his name representing and freeing wrongly incarcerated prisoners, and his passion is on display here.

He shows how the war on drugs, mandatory sentencing guidelines and other tough-on-crime measures, disproportionately affects Black people. You can hear stories of people wrongfully convicted in a section designed like a prison visitors wing. Video screens show convicts waiting to speak, and when you pick up a phone, they share their stories of injustice.

The museum ends with a small area devoted to art, and space for reflection. Take a few minutes here. The material you’ve just absorbed is complex, challenging and heart breaking.

The powerful ‘Lynching Memorial’

The lynching memorial is the emotional center of the complex, and although it’s abstract, prepare to be shaken by your visit.

The entrance leads by several sculptures and then heads up a gravel path to the memorial, which consists of 800 weathered steel boxes hanging in an open canopy. Each marker represents a county or jurisdiction that experienced a lynching between 1877 and 1950. On the boxes you’ll find the names of forgotten victims, like Henry Smith of Lamar County, Texas. The young man was accused of killing a white girl, and then hanged and maimed in front of a crowd of 10,000.

There’s also Elizabeth Lawrence, lynched in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1933 after she scolded children for throwing rocks. And thousands more.

The information comes from a study that documented more than 4,000 lynchings, which the researchers classify as racial terror killings.

In most cases, the victims were grabbed by a mob and publicly killed, usually by hanging, but also by gunshot or drowning. Sometimes it occurred in public squares, where vendors sold refreshments. Gawkers claimed pieces of clothing or body parts as souvenirs. Occasionally, commemorative postcards were printed.

While the memorial recounts these details in brief side panels, its visual impact is devastating. The markers hang at eye level, but as visitors proceed through the monument, the floor slopes down. Soon the monuments are suspended above, forcing one to look up.

Eventually, hundreds of slabs hang ahead like bodies. A visitor becomes the spectator, like those that came out to watch lynchings, bearing witness to brutality.

Outside the central canopy, a replica of every marker lays in a field. Each jurisdiction is invited to claim their monument to bring home for public display. The intent is clear. As Stevenson said when the monument opened: “Our memorial will become a report card about which communities have owned up to their history.”

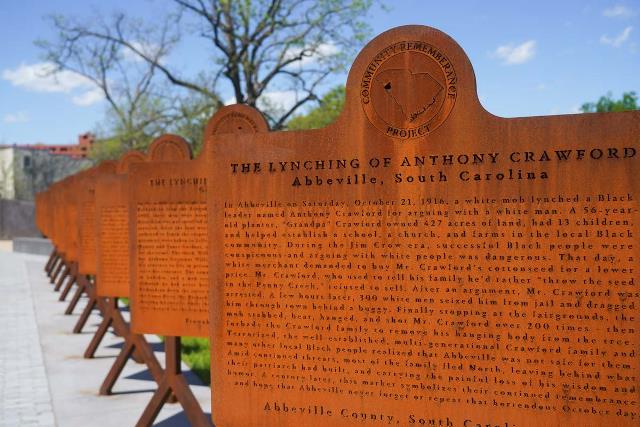

Nearby is a new Community Remembrance section. As testimony to the power of the memorial, since its opening nearly 50 markers have been erected in 20 states, recounting local lynchings. Steel replicas of these markers are on display, along with a sculpture dramatizing local residents advocating to remember the forgotten stories.

“My hope, my vision, is that there’s a marker in every lynching site in America,” Stevenson said.

The lynching memorial design was inspired by South Africa’s Apartheid Museum and Germany’s Holocaust Memorial.

Across the street from the lynching memorial stands the Peace and Justice Memorial Center. It houses an auditorium, which hosts a presentation about the memorial at 2:30 p.m. on Mondays, Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays. It also has another monument commemorating two dozen people killed killed during the 1950s, showing that racially motivated murders continued.

Guidebook

While the ‘Lynching Memorial’ can be overpowering, Montgomery has much more to offer. Make sure leave time to visit Montgomery’s other civil rights sites too.

Montgomery travel info: Download a free MP3 Civil Rights walking tour and map here

Book a guided tour

Wanda Battle offers such a moving tour that she often leaves her groups in tears. Likewise, Jake Williams who participated in the Selma-Montgomery march provides a memorable tour of his city.

Ann Clemons, another gifted guide, can customize tours through her company,

Or consider a three-day tour that visits Montgomery, Selma and Tuskegee.

Hotels

Lodging can be tight here during special events and when the Alabama legislature’s in session.

Trilogy Hotel One of the city’s newest lodgings is one of its best. Located walking distance from downtown civil rights sites, the hotel offers comfortable room in beautifully restored warehouses. 108 Coosa Street, Montgomery, 334/440-3550.

Springhill Suites A handsome and comfortable hotel set inside a renovated building, just a few blocks from the Legacy Museum. 152 Coosa Street, Montgomery, 334/245-2088.

Renaissance Montgomery It’s one of the city’s newest, busiest and biggest hotels, and most comfortable. Near the riverfront park and convention center, and walking distance to most sites. 201 Tallapoosa Street, Montgomery, 334/481-5000.

Red Bluff Cottage Bed and Breakfast For real Southern hospitality, try something homier. This five bedroom B&B features antiques and wireless Internet. 551 Clay Street, Montgomery, 334/264-0056.

Dwella at Kress on Dexter A newly opened condo hotel within walking distance of the major civil rights sites.

Literature lovers, English majors and fans of The Great Gatsby can sleep in the former home of author F. Scott Fitzgerald. Two AirBnBs, located in the home Fitzgerald shared with his wife in 1931-32, include a record player with jazz albums and a sun porch overlooking the city’s Old Cloverdale neighborhood. Check out the Zelda Suite and the Scott Suite, which include a record player with jazz albums and a sun porch overlooking the city’s Old Cloverdale neighborhood.

Dining

Part of the Equal Justice Initiative Legacy Pavilion complex, this is not a typical museum restaurant. The Auburn, Alabama, eatery has quickly developed a Montgomery following for its chef-prepared soul food. 450 North Court Street. 334/386-9116

Look for lobbyists wining and dining legislators at this Montgomery institution. The oyster salad is classic. 8147 Vaughn Road, 334/244-0960.

Why come to Alabama for hotdogs? Because there’s a rich tradition of Southern hotdog joints. This classic diner has served up delicious redhots, fries and burgers for nearly a century. 138 Dexter Avenue, Montgomery, 334/265-6850.

Montgomery’s oldest take-out barbecue stand is a community institution.

In its early years, the NAACP held secret meetings in its back garden, where volunteers taught African Americans how to read and write in order to take the poll tests, created to discourage them from voting. They also printed out fliers for protests.

Now it’s a place for barbecue standards, and also a Southern specialty: A pig’s ear sandwich! Also try Barbara Gail’s Neighborhood Grille, which is run by the same family. Located on the Selma to Montgomery Trail, it’s a great stop for a diner breakfast.