A Mississippi civil rights museum explores the state’s long, deadly struggle for equality

In the struggle for civil rights, it always came down to Mississippi.

The state was the site of some of the most notorious and violent moments of the movement, including the murder of Emmett Till, the killing of civil rights workers during Freedom Summer, and the imprisonment of the Freedom Riders.

For decades, the state refused to acknowledge this history, but in 2017 it opened an extraordinary complex making it one of the Mississippi civil rights museum one of the best in the country.

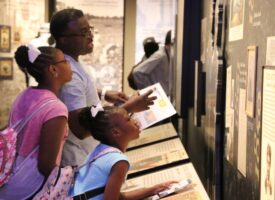

The Mississippi Civil Rights Museum is reason alone to visit the state capital, making an important stop for anyone interested in the US’ struggle for racial equality, and is simply incorporated into a civil rights tour of the South.

Jackson is an easy three-hour drive from Birmingham. And after Jackson, it’s possible to pop up to Oxford to visit Ole Miss, or the Greensboro area to see sites associated with Emmett Till, and from there, you’re in easy range of Memphis’and the Lorraine Motel.

So take time to delve into the museum. Its companion Mississippi History Museum is also worthwhile, and thoughtfully curated. Standout exhibits include an examination of the juke joint, and the state’s surprising multicultural heritage. But you’ll want to devote your time to the Civil Rights Museum.

Museum layout

The museum is shaped has several galleries connecting to a center hub. For many, the its blunt presentations will be shocking.

The introductory gallery explains how enslaved Africans were first brought to the territory by colonialists in the 17th Century and explores the violence they faced. Walking through the galleries, recordings lash out of the darkness with racial taunts: “Boy, get off that sidewalk,” and “Gal, you know you say thank you to me.”

But other traumas were far worse. Six pillars list lynchings dating back hundreds of years.

One alcove, shielded from younger visitors, flashes historical photos of men hanging from trees, listing their names, locations and dates of death. The images are projected at an angle, so viewers unconsciously must tilt their necks, like those of the victims.

Throughout the galleries, small immersive theaters cover key moments from the modern civil rights era, which gained a foothold as African-American soldiers stationed overseas during the Second World War returned to find discrimination and segregation back home.

Exhibit planners use multimedia theaters showing archival footage of trials, protests and funerals, and artifacts like hooded Ku Klux Klan robes, a burned cross and the Enfield rifle that took the life of Jackson civil rights leader Medgar Evers in his home’s carport.

Must-sees include the Emmett Till section, anchored with a theater featuring Oprah Winfrey, a Mississippi native. She narrates a short film about the 1955 killing of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy visiting from Chicago who was accused of flirting with a white grocery store clerk.

A few days later, he was kidnapped, and his barbed wire-wrapped body was soon found in the Tallahatchie River.

After Till’s death, his mother gave him an open-casket funeral, and the shocking images of his maimed body were printed in Jet magazine, launching the modern civil rights movement. The museum displays the original magazine pages, along with the doors of the Bryant’s Grocery & Meat Market.

But the museum is hardly a collection of dusty memorabilia. It uses historic footage, interactive displays and innovative exhibits to convey its story.

Another section addresses the assassination of Evers, who was shot in the back by a white supremacist. The father of three staggered to the door of his home, where his family found him bleeding to death.

The museum also celebrates the movement that ultimately eliminated legal segregation.

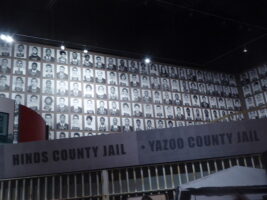

Freedom Rides

One gallery, lined with hundreds of mugshots, honors the 1961 Freedom Rides, the bloody crusade to protest segregated transportation facilities in the South. Hundreds arrived in Jackson by bus, train and plane were methodically arrested and sent to the infamous Parchman Farm prison, located on a former plantation. Their mugshots now line museum walls, and an interactive gallery reveals the stories of many, including the late Georgia congressman John Lewis, then a 21-year-old college student.

Nearby, an emotional video presentation explores the murders of 1964’s Freedom Summer campaign to register African-American voters. Black state resident James Chaney and white student volunteers Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman disappeared on a June afternoon. Their bodies were later found by the FBI, buried in an earthen dam near Philadelphia, Mississippi, and the footage of Chaney’s eulogy by a fellow activist still resonates across the decades as a cry for justice.

But the museum digs far deeper than these major exhibits. Nearly every Mississippi city and town had its own racial protest, and many get their first widespread exposure in these galleries.

One display outlines the ‘wade-ins’ in 1959, 1960 and 1963 to desegregate the Gulf Coast beaches of Biloxi. Another recalls the ‘read-in’ at Jackson’s whites-only public library, led by the Tougaloo Nine, a group of students from the city’s historically black college.

A touch screen explores the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission, a domestic CIA of sorts, which spied on citizens believed to support desegregation. Other exhibits chart the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and their terrorizing night rides through black communities.

Light at the center

Although the stories are grim, there is the sound of hope in the air. At the heart of the museum, a towering 40-foot sculpture called This Little Light of Mine pulsates every 30 minutes with gospel songs that inspired protesters and became a soundtrack to the era.

When visitors are drawn by the music to the center gallery, they trip electronic sensors. As the crowd swells, lights outlining the sculpture glow and intensify, and the music builds to a crescendo from individual voices to a choir.

Myrlie Evers-Williams, the widow of Medgar Evers who delivered the invocation at President Barack Obama’s second inauguration, spoke at the museum’s dedication. She says the symbolism is clear. “You hear the sounds of horror, but you hear the sounds of coming together.”

Guidebook

See more Jackson sites here.

For more information on Jackson, see Visit Jackson‘s online guide, including a comprehensive, downloadable civil rights driving tour.

Dining

For an authentic taste of the South, try a pig ear sandwich from the Big Apple Inn in Jackson’s Farish Street Historic District. It’s also a place to try southern tamales. Medgar Evers once had an office above the restaurant.

Or try the equally famous blackberry cobbler from Bully’s Soul Food.

You’ll find authentic flavors of Africa at Sambou’s African Kitchen, a James Beard Award nominated eatery that features Gambian cuisine.

Jackson offers some top dining options, which mix Southern cooking with modern techniques.

Favorites include: Elvie’s and Walker’s Drive-Inn, both upscale, James Beard-honored restaurants; Saltine, a fun oyster bar in a former school building; and Manship Wood Fired Kitchen, which combines Southern and Mediterranean flavors.

Lodging

For a treat, plan a visit to one of the best stay’s in the South, the historic Fairview Inn, which regularly hosts visiting celebrities and VIPs in Southern chic comfort. If nothing else, try to stop by for their Sunday brunch.

You’ll find a full array of chain hotels, including the top ranked Hilton Garden Inn Jackson Downtown, in a restored office building.