Danville civil rights museum exhibit honors ‘Bloody Monday’

The violent police attacks in Birmingham in May 1963 are known around the world. But few people have heard of the equally brutal assaults that came weeks later in Danville, Virginia.

The protests, immortalized as Bloody Monday, saw mass arrests and beatings as police and newly deputized garbage workers attacked peaceful demonstrators with firehoses and billy clubs, sending dozens to the city’s segregated hospital. And hundreds to jail.

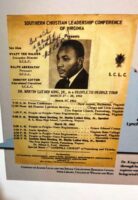

A Danville civil rights museum exhibit tells the story, introducing us to local students, ministers and citizens who confronted the city’s entrenched racism and segregation. And while national leaders from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference encouraged them, the movement was largely Danville based.

Martin Luther King Jr. visited Danville four times during 1963, part of a Southern Christian Leadership Conference campaign. He described the city’s law enforcement as among the most violent in the South.

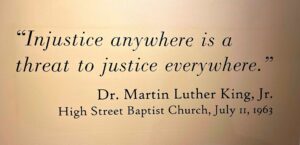

“Very seldom, if ever, have I heard of a police force being as brutal and vicious as the police have been here in Danville, Virginia,” he said, adding: “As long as the Negro is not free in Danville, Virginia, the Negro is not free anywhere in the United States of America.”

John Lewis even mentioned Danville in his speech at the March on Washington, describing the city to the crowd of a 250,000 as “a police state.”

Forgotten protests

But today the protests are little known.

Only in recent years has the city begun to fully recognize the legacy, adding a small civil rights exhibit to its local museum and placing historic markers around town. Along with the museum, you’ll want to drive by High Street Baptist Church, a congregation where King spoke twice, and where police broke through a locked doors to arrest protesters.

Danville isn’t easy to reach. It’s located near the Virginia-North Carolina border, far from Interstates. But for travelers passing through the region, it’s worth a visit. And it’s an easy addition to a mid-South tour, lying directly on the route between the Moton Museum in Farmville, Virginia, and the International Civil Rights Center in Greensboro, North Carolina, two of the most important civil rights sites in the Upper South.

It’s also about an hour’s drive from the birthplace of Booker T. Washington, a National Parks Service site, near Roanoke, Virginia, a city worth exploring as well.

Danville’s a quiet city of 41,000, but it has a rich history. The region prospered as a tobacco processing center and later as the home to a busy fabric mill. It also has a notable Civil War heritage, and is considered the last capital of the Confederacy. Indeed, a confederate flag flew in front of the city museum until 2015, only coming down after the mass-shooting at the Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

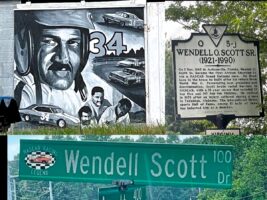

Despite Danville’s small size, its Black community has had a large impact. Former residents include opera diva Camilla Williams, and NASCAR Hall of Famer Wendell Scott.

Danville civil rights museum exhibit

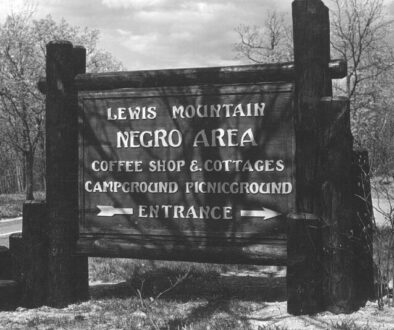

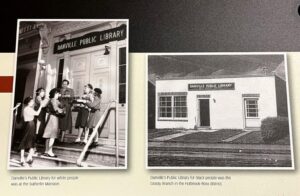

There’s no escaping the Civil War legacy here. The civil rights exhibit’s located in the basement of the Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History, also called the Summerlin Mansion. Confederate President Jefferson Davis stayed in the home, and held the last meeting of the Confederate cabinet in the building. The museum preserves the room where Davis slept, offers a display on the Confederate battle flag, and has a meeting room still used by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the organization responsible for saving the mansion – and for placing statues of Civil War generals across the South.

The mansion also played an important role in Danville’s civil rights history when it was the city’s Whites-only public library,

In 1960, inspired by the Woolworth’s counter sit-in in nearby Greensboro, North Carolina, a group of Black high school students tried to integrate the library, which had 10 times the number of books as the city’s Blacks-only library. The librarian booted them out and the city responded by closing the library for the summer. When it reopened, Blacks were allowed in, but the library had removed all chairs and tables, making it impossible for anyone — Black or White — to study there. It was a move reminiscent of how many Southern cities closed their parks, swimming pools, and even public schools, instead of integrating them.

The struggle renewed in 1963, starting with a New Year’s Day sit-in at a local Howard Johnson’s restaurant that led to the arrest of the Rev. Lawrence Campbell of Bibleway Cathedral and four other local ministers, who had formed the Danville Christian Progressive Association. The city landed on the radar of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and in March, Martin Luther King Jr., spoke to a crowd at 2,500 at the Danville City Auditorium.

On May 31, Black residents began peaceful protests against the city’s segregation policies, and municipal hiring practices. At first, they were ignored by the local press, but things quickly heated up. The next week, 125 demonstrators occupied City Hall, leading to the indictment of organizers, The police used a pre-Civil War law that outlawed actions inciting “the colored population of the state to acts of violence against the white population.”

By June 8, more than 300 people had been arrested. The city was simmering, and in a few days it would boil over.

Violence erupts on Bloody Monday

The protests came to a head on June 10, a day now called known as Bloody Monday. In the morning crowds sang freedom songs and marched through the downtown streets in support of those who had been arrested. Police, assisted by newly deputized garbage workers, firehosed the demonstrators near City Hall. The protesters, which included children, were washed down the street by the high-pressure spray. Others were beaten. That evening, police attacked a peaceful prayer vigil with clubs and hoses.

Nearly 50 people were hospitalized, making it one of the most violent police attacks of the civil rights movement. Southern Christian Leadership Conference volunteers and college-age protesters rushed to the city to help. They were to be housed in local homes, but officials passed a law making it illegal for Blacks and whites to stay in the same house.

A month later, King returned to the city, along with other notables like John Lewis, and the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth. Speaking at High Street Baptist Church, King condemned the police violence.

Protests continued for the next few months, and one of King’s top deputies, the Rev. C.T. Vivian came to the city to train protesters in non-violent strategies. Eventually this led to real gains. Danville began to integrate its schools in August, hired its first Black policeman, began to register Black voters and adopted fair employment laws.

King returned again in mid-November for another memorable speech at High Street Baptist. He was interrupted by a neo-Nazi, and King famously let the man speak his mind. King and SCLC had plans to ramp up the campaign in Danville in 1964. But later that month, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, and the protests were suspended.

Now, nearly 60 years later, many of the former protesters still live in town. The exhibit does an excellent job telling their stories, and celebrating their bravery.

A Black NASCAR legend

Before you leave Danville, drive by the home of Wendell Scott, the first Black inductee to the NASCAR Hall of Fame. His story got wide attention in the 1977 movie, starring Richard Pryor. Not only is the street named after him, but there’s a mural featuring him in his racing glory days. Just set your GPS for Wendell Scott Drive.

Booker T. Washington Birthplace

If you’re passing through the region, consider a detour to the birthplace of Booker T. Washington. The National Monument, a National Parks Service site, preserves the tobacco plantation where Washington grew up in slavery. It’s here as a nine-year-old that he learned that he had been freed by the Emancipation Proclamation and the defeat of the Confederacy.

The young boy choose the name Washington, and set his sights on the future. He earned a degree from Hampton Institute in Virginia, and then went on to found what is now Tuskegee University in Alabama, home to the famed Tuskegee Airmen.

The farm is 55 miles away, about an hour’s drive from Danville, and not far from Roanoke, Virginia. Looking at the modest setting, it’s astounding to know that Washington went on to become one of the most influential Black leaders in the nation.

Danville Guidebook

Download the Distrx app (App Store or Google Play), which includes a walking tour of civil rights sites in the Danville River District.

Local historian and genealogist Karice Luck-Brimmer offers personal tours of Danville’s Black history sites through her company Our History Matters.

Learn more about Danville sites, hotels and services here.

Dining

You’ll find Crema & Vine, one of the city’s nicest restaurants across the street from the Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History. The cafe, wine bar and coffee shop, serves pizzas, salads and sandwiches.

Lodging

Surprisingly, Danville home to a stylish boutique hotel, The Bee. Located in the River District, it occupies the building that once housed the local newspaper, The Danville Register & Bee. Book a room here.