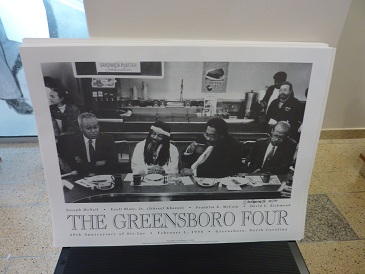

Four college dorm-mates just wanted to sit down and order a cup of coffee and a glazed doughnut. By the time they were served months later, they had introduced the phrase “sit-in” to the dictionary and helped demolish Jim Crow laws across the South.

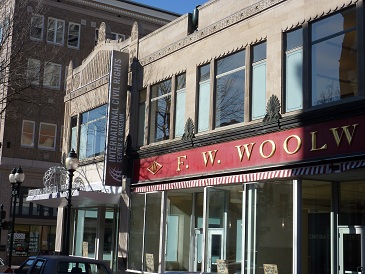

The International Civil Rights Center, one of the top museums in Greensboro, NC, recalls the courageous story of the Greensboro Four.

The museum is only about 90 miles from the Robert Russa Moton Museum in Farmville, Virginia, which preserves the Blacks-only high school where the protest began. It and the Greensboro museum are the two most important civil rights sites in the upper South. On the way, consider stopping in Danville, Virginia, site of one of the most violent police resgponses to civil rights protests, which became known as Bloody Monday.

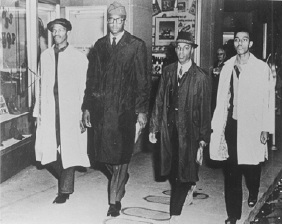

In Greensboro, take a moment to put yourself in the shoes of the protesters. The young men, freshmen at North Carolina A & T College, were idealistic and angry. The indignity of segregation especially stung Joseph McNeil, who watched his humanity stripped away as he traveled from his home in New York back to college after Christmas break in 1960. In Philadelphia, he could order food like anyone else at the bus station cafe, but by the time he reached Richmond, Va., he was no longer served — his rights had disappeared.

When he arrived back at his dorm, he joined three friends Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair, Jr. and David Richmond, to take a stand. History now remembers them as the Greensboro Four.

The museum which opened in the former Woolworth’s store on the 50th anniversary of the sit-in, does a masterful job of putting visitors in the protesters’ place. An introductory film lets you watch as the students plan their action in Room 2128 of Scott Hall. (The museum has the original door.)

Visitors then leave the room and step on an escalator leading to the lunch counter. Like the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., you’re put in the footsteps of the participants. Your heart thumps as the escalator climbs. What would I do, you ask yourself. Would I be as brave as those four young men?

The counter itself is a step back in time. It has been renovated to recreate its 1960 appearance. Signs advertise slices of cherry pie for 15 cents, and a turkey dinner for 65 cents. Films projected behind the counter depict the event.

You watch the waitresses refuse service, and the reaction of the agonized manager who realizes the students don’t plan to leave. Some whites taunted the men, while others urged them on.

The protests continued for months. Other students joined in, and effectively closed down the counter. The protest spread to other stores in town and, as newspapers picked up the story, across the South.

During the school’s summer recess, local high school students took up the cause. Finally by the end of July, Woolworth’s relented and offered service to everyone.

While the lunch counter is the heart of the museum, the institution’s reach is broader.

It depicts the full scope of segregation, from hotels to transportation, and touches on the other civil rights protests that defined the era.

Some visitors may be put off by the “Hall of Shame” at the entrance, which shows graphic photos of victims of racial violence. It’s possible to bypass this area – ask a museum employee to show you the detour. The museum also offers lectures, children’s story hours and a research library.

North Carolina A & T State University remembers

A half-century later, the protesters’ alma mater honors their bravery. The Greensboro Four statue shows the young men striding purposely away from campus toward downtown and their meeting with history.

A bit of trivia: while the four were walking to the counter, they realized in horror that they did not bring any money. They weren’t sure what they would do if they were actually served.

A golf course that made history

Before the Greensboro Four, there was the Greensboro Six, a group of African-American golfers who defied segregation and played at city-owned Gillespie golf course.

A statue on the on the lawn of the Old Guilford County Courthouse, 300 W Washington St, Greensboro, NC 27401, now honors dentist Dr. George Simkins Jr. The former president of the local NAACP chapter, he led efforts to desegregate local hospitals — and the golf course.

Guidebook

Check out other Black cultural sites and museums in Greensboro NC.

Greensboro is now a lively college town with an active arts and music scene. For city information, check with the tourism bureau.

The city’s a 90-minute drive from Charlotte, 300 miles from Washington, D.C., and 330 miles from Atlanta

Lodging

O. Henry Hotel is named for the famed short story writer, who was from town. Its clubby, comfortable atmosphere is all the more surprising since it’s located in a suburban office park. A nice touch: complimentary Oh Henry! candy bars at the reception desk. 624 Green Valley Road,Greensboro, NC 27408.

Proximity This sister property to the O. Henry is built to the latest environmental standards. Enjoy the loftlike rooms and sleek design. 704 Green Valley Rd, Greensboro, NC 27408. Rates from $169.

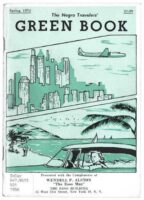

The Historic Magnolia House Motel, a former Green Book site, has four rooms decorated in period 1950s and ’60s style. See more details below.

Dining

If you’re in town on Sunday, you’ll want to stop for brunch at the Historic Magnolia House Motel. The former Blacks-only hotel was featured in the famed Negro Motorist Green Book, which guided travelers to hotels and restaurants that accepted Black guests.

If you’re in town on Sunday, you’ll want to stop for brunch at the Historic Magnolia House Motel. The former Blacks-only hotel was featured in the famed Negro Motorist Green Book, which guided travelers to hotels and restaurants that accepted Black guests.

It was once one of the few hotels between Richmond, Virginia, and Atlanta to accept Black guests.

Celebrities who stayed here include: James Brown, Ray Charles, Ike and Tina Turner, and Jackie Robinson.

Other Greensboro Green Book sites include:

- Plaza Manor Hotel, a boarding house, 511 Martin St., Greensboro

- Harris East End Gulf, service station, 2011 E. Market St., Greensboro

- Club Fantasy, club, 603 E. Washington St., High Point

Black-owned Also, here’s a list of 20 Black-owned restaurants in Greensboro, with everything from Caribbean to Ethiopian to food trucks.

Barbecue North Carolina is barbecue country. Check out the Tarheel State’s version at Stamey’s. The closest one is at 2206 High Point Road.

November 27, 2022 @ 8:20 am

I have a friend whose grandfather and great uncle escaped a lynching in Guilford County during Jim Crow times. The brothers separated to Increase the chances that one would survive. Grandfather went to Pittsburgh, where my friend was born in the fifties.

I don’t know how much of this story she can tell, but I have thought about encouraging her to share somewhere. It sounds like her family was dramatically affected by conditions set out on your Wall of Shame.

I am white. I gave my great aunt’s papers to Georgia Tech, where they were digitally located by her alma mater, UNCG, and were accessed by the writer of Hidden Figures. You just never know how all our stories fit together.