We all know the civil rights giants. Martin, Rosa, and Malcolm don’t even require a last name.

But here’s one you’ve probably never heard of: Barbara Johns.

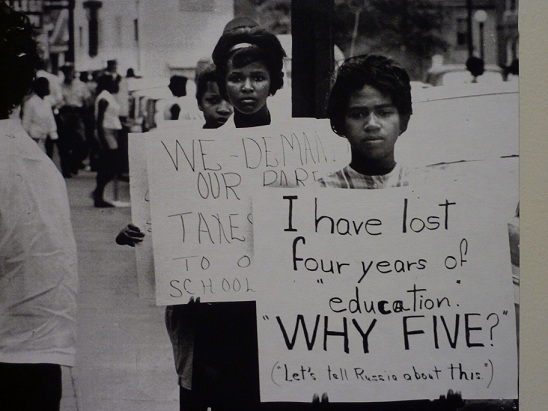

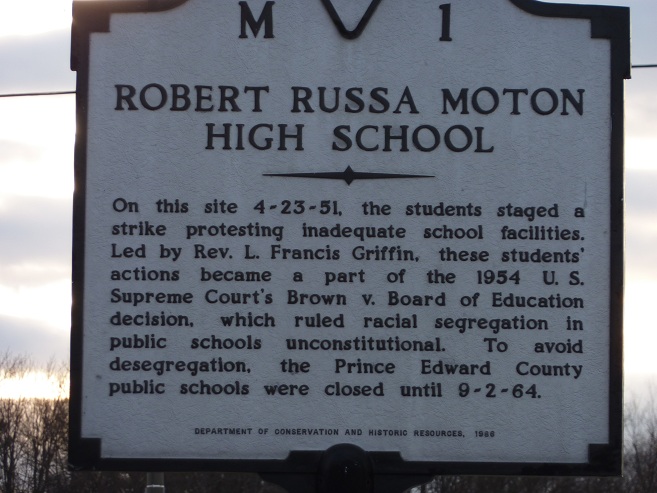

The 15 year-old Virginia high school student launched a protest that ultimately reached the U.S. Supreme Court. For five years, the public schools in Prince Edward County, Va., simply shut down because they refused to mix Black and white students. The remarkable story — largely unknown today even in Virginia — is told at the Robert Russa Moton Museum in Farmville, Va., about 65 miles southwest of Richmond.

The Robert Russa Moton Museum preserves the Blacks-only high school where the protest began. The displays are modest now, but will receive a multi-million-dollar upgrade in late 2010. This will require the facility to close for several months, so check to make sure it’s open before making the trip. Moton’s only about 90 miles from the new Greensboro. N.C. museum commemorating the famed Woolworth’s counter sit-ins, making for an easy civil rights itinerary.

In Farmville, as in Greensboro, the protest was led by seemingly fearless students. The Black high school had been built to hold 200, but by 1951 enrollment had reached 450. It lacked a gym and science labs. Classes were held in closets, on parked school buses, and in leaky tar paper shacks heated by pot-bellied stoves like a scene out of a pioneer history book.

Johns, who served on the school debate team, had visited other schools for tournaments and knew conditions were much worse at Moton than at other Black schools. She decided to do something about it.

The school was run by a no-nonsense principal, so Barbara and a few friends concocted a plan to lure him off campus. A male classmate called the school and, imitating the voice of a downtown store owner, told the principal that some of “his boys” were causing trouble, and if the principal didn’t do something about it, the police would be called.

As soon as the principal left the school, Barbara distributed a note to all classes, summoning the entire student body to the auditorium. Teachers were instructed to stay in their classroom. She signed the note B.J. — her initials, and also those of her principal.

When the students arrived, Barbara — until then, a quiet, unassuming student — stood up in front of her classmates and urged them to join her in a walk-out. She reasoned that their parents couldn’t protest because they would lose their jobs. It was up to the students to lead the effort.

School officials were furious, and refused at first to meet with the protesters. Barbara sought help from NAACP lawyers from the state capital, Richmond. They told her that the national organization was planning a lawsuit against segregation and urged her to join the fight.

The students returned to class after two weeks, but ultimately, the Farmville case was combined with four other school segregation suits — from Washington D.C, Delaware, South Carolina, and Topeka, Kansas — to become the famed Brown. V. Board of Education case that ultimately found “separate but equal” public facilities were unconstitutional.

Barbara eventually left Farmville because her family feared for her safety. In a great irony, she was sent to finish high school in the “calm” city of Montgomery, Alabama, where her uncle was the preacher at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church — which would soon become Martin Luther King’s home pulpit and the epicenter of the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

But Farmville’s amazing story doesn’t end there.

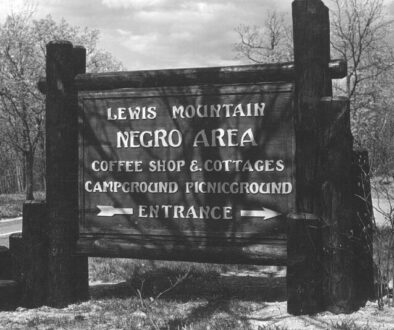

Back in Virginia, officials first ignored the Supreme Court’s ruling against school segregation. When forced to integrate, it adopted a strategy of massive resistance closing all its schools. Many white children were soon enrolled in quasi public academies, but the 1,700

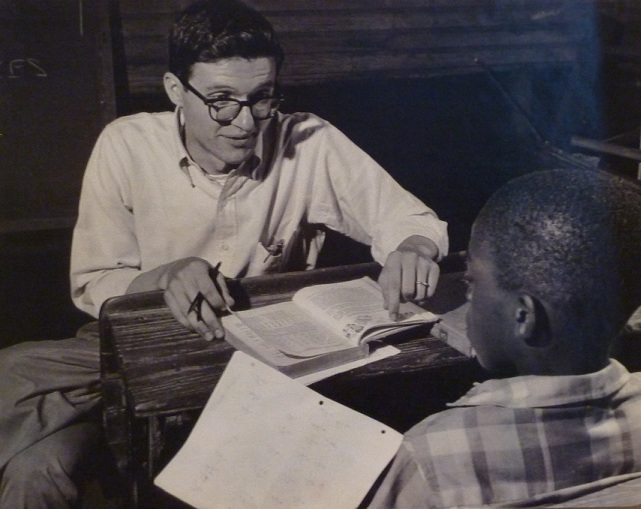

Black students had no similar option. Some families sent their children off to live with relatives in other cities. And during the summer, college students from the North came to Farmville to teach classes.

In total, Prince Edward County went without public schools for five years. Those children without an option for education became what is called now “the crippled generation” since they missed so many years of school.

The resistance came to an end in 1964. President John F. Kennedy is reported to have said that there were three places on the planet without public education, North Korea, Cambodia and Prince Edward County, Virginia, and his administration worked with local officials.

In total, Prince Edward County went without public schools for five years. Those children without an option for education became what is called now “the crippled generation” since they missed so many years of school.

The resistance came to an end in 1964. President John F. Kennedy is reported to have said that there were three places on the planet without public education, North Korea, Cambodia and Prince Edward County, Virginia, and his administration worked with local officials to reopen their schools.

Barbara Johns became a school librarian, and died in 1991 of cancer. Her statue is a central figure included in Virginia’s Civil Rights Memorial, dedicated in 2008 on the capital grounds in Richmond. Her story should be known by every school child in the nation.

Perhaps it’s more than an oversight. Maybe school leaders are reluctant to teach their pupils about the power of a student-led protest.

Guidebook

Virginia travel info The Moton museum is the centerpiece of Virginia’s Civil Rights in Education Heritage Trail

Farmville’s extensive guide to African-American heritage sites

Dining

The Fishin’ Pig Popular BBQ and Southern seafood spot

North Street Press Club Burgers, salads and Asian fusion

Hotel

The boutique Hotel Weyanoke originally opened in 1925. Now restored, it has a convenient downtown location.

Hampton Inn Farmville Although a college town, lodging’s limited. This chain offers expected amenities and gets high ratings for service.

October 13, 2021 @ 5:40 pm

Hello— I’m very much looking forward to coming to your museum in a couple of weeks. I just wanted to point out, if you don’t mind, a concern with the introduction to the museum on your landing page. It reads “We all know the civil rights giants. Martin, Rosa, and Malcolm don’t even require a last name.”

Though Malcolm X wanted to empower people of color and was an advocate for human rights in general, he was not a supporter of the American civil rights movement. Like Marcus Garvey before him, he wanted black Americans to return to Africa, and in the meantime to form their own separate nation within America. He believed fervently in segregation, not integration. He even criticized Dr. King and the civil rights movement for their advocacy of both integration and nonviolent protest.

Sadly, many people don’t understand what beliefs Malcolm actually promoted, and what’s more, don’t realize that those beliefs ran counter to nearly everything that American people of color and their allies have fought for. He has been lumped in with other civil rights pioneers only because he was a very visible presence until his assassination by Nation of Islam members in 1965.

I don’t mean to offend anyone by writing this, but I would hope that one of the countless other heroes of the civil rights movement be substituted for Malcom X, or even that the sentence be changed, as clever as it is, given that there have been so many other true advocates of pluralistic civil rights whose names are less well-know but who were no less important. (Also note that by the ’60s Malcolm was using Shabbaz as his last name.) Unlike Dr. King, Malcolm was an extremely divisive figure. Perhaps consider Medgar Evers, one of the first in the movement to be murdered at the hands of racists. Or even go back to the great Frederick Douglass, who arguably started it all. Thanks for listening.

Sincerely,

Russell Hart