Greenwood Rising: the Tulsa Massacre Museum Honors Black Wall Street

Step into the dark room, and you’re transported back a century to a moment of horror. Families huddle in terror as roaming gangs of armed men attack their neighborhood, setting fire to homes and businesses, shooting indiscriminately into crowds, and even dropping dynamite from a plane.

When the violence subsided, Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood, the so-called Black Wall Street, was left a smoldering ruin. Survivors were placed in detention camps and ordered to clear the clutter. The neighborhood, once home to banks, restaurants, theaters and the nation’s largest Black-owned hotel, the J.B. Stradford, had been destroyed.

As devastating as it was, it’s only recently that people have begun to hear about Black Wall Street, and the Tulsa Massacre, which occurred on May 31 and June 1, 1921. For most of the last century, it wasn’t taught in Oklahoma schools, let alone anywhere else. Awareness has come thanks to a 2001 state commission report that documented the incident, and, it must be admitted, the HBO series Watchmen, which featured the dark moment of U.S. history in 2019. Even now researchers are still finding the graves of victims.

Tulsa Massacre museum

The story, told at the new Tulsa Massacre museum, is shocking—an estimated 300 dead, the first aerial bombing of a U.S. city, the machine-gunning of homes, and the destruction of an entire neighborhood leading to more than $200 million of damage based on current values. Although many residents had insurance, officials altered laws so that claims would not be paid.

The museum, called Greenwood Rising, gathers the shards of the story, showing what was lost in the eruption of racial violence—and what the Black community was able to retain. Using multi-media screens and projections, it puts visitors in the streets of Greenwood, both during its heyday, and then at its destruction. The final of the museum’s eight spaces, the “Journey to Reconciliation,” urges visitors to visualize how Greenwood, and the greater community, might heal as it moves forward.

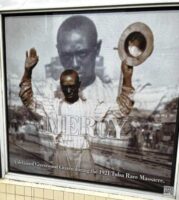

The 11,000-square-foot museum brings new life to the heart of the Greenwood. A few blocks away, visitors can pause for reflection at the John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park, which honors the famed historian, a Black Tulsa native, and features statues commemorating the massacre. A new “Pathway to Hope,” with art and community photos, connects the park to Greenwood, where visitors find Black Wall Street gift shops, a community center, and the historic Vernon Chapel AME church, built after the massacre.

For civil rights travelers, Tulsa makes an important mid-way stop between the Brown v. Board of Education site in Topeka, Kansas, and the Little Rock Central High School visitors center in Arkansas.

Innovative exhibits

The museum, which opened in 2021 on the 100th anniversary of the massacre, uses a story-telling approach to bring visitors into the narrative. The exhibits are designed by the Local Projects design studio, which also created the displays at the National September 11 Memorial & Museum.

Visitors start with a short inspiring video based on Maya Angelou’s poem “Still I Rise,” which sets the tone for the visit. Then comes an introduction to Greenwood through a clever re-creation of a 1920s neighborhood barber shop. As guests sit in barber chairs, they can watch three Black barbers, depicted as holograms, describe how Greenwood rose to prominence after its founding in 1906.

Next, the museum tells how Blacks came to Tulsa, and the challenges they faced. The room, called the “Arc of Oppression,” outlines how government and history systemically oppressed Black Americans. Recognizing that some displays, like slave shackles, a photo of a lynching and a Ku Klux Klan robe, may be too intense for visitors, the museum’s designed with an “emotional exit” to offer a path out of the room.

The massacre was not unprecedented. In the years leading up to the attack, mob violence against Black communities had swept the country. One of the first incidents occurred in Wilmington, N.C., in 1898. The killings and destruction seemed to reach a peak during the “Red Summer” of 1919, when mobs in more than three dozen U.S. cities attacked Black communities.

Then came Tulsa.

When visitors enter the heart of the massacre, they’re taken to Memorial Day weekend, 1921. The violence, we’re told, was prompted when a 19-year-old black man, a shoe shiner named Dick Rowland, was arrested for assaulting a woman, Sarah Page, 17, who was working as an elevator operator. Reports vary, but it’s likely it was an accident. He may have bumped into the teenager or stepped on her foot, causing her to scream. Nonetheless, the encounter was reported in the newspaper, and Rowland was arrested for rape.

Fearing a lynching, an armed group of men, many of them Black World War I veterans, rushed to the jail to protect him. They met a group of white men, and a confrontation began. (Rowland was never charged with a crime, and is believed to have escaped Tulsa safely.)

The white posse grew to a mob of an estimated 2,000, and descended on Greenwood, burning and looting buildings. Included in the mob were many men who had been deputized that evening by the Tulsa police to attack Greenwood. Black residents, who were trying to protect their community, were rounded up by police and the National Guard, which had been mobilized.

Visitors witness the violence on large projection screens that show homes devoured in flames. Narration based on oral histories describe the terror. By the next morning, most of Greenwood had been destroyed, and was under martial law. The commission report said the damage included one dozen churches, five hotels, 31 restaurants, four drug stores, eight doctor’s offices, more than two dozen grocery stores, and the Black public library. But the damage was greater: a community had been destroyed.

The final rooms may come as a surprise. Greenwood, we learned, did bounce back from the massacre, and continued to thrive through the 1950s. As in so many communities, it was the construction of a highway, Interstate 244, that ultimately split the neighborhood in two, and largely destroyed it. Locals say the so-called urban renewal was actually “urban removal.”

Around Greenwood

After visiting the museum, take time to explore the adjacent blocks of Greenwood Avenue, and patronize the Black-owned gift shops and restaurants.

Check out the Greenwood Cultural Center, which often runs special programs and exhibits.

A clever walking tour, accessed through the Greenwood Rising XR (extended reality) iPhone app (or Google Play) lets you use your cellphone to see what Greenwood looked like during its heyday, re-creating buildings, crowds and newsstands that once lined the streets.

You can book a guided tour through the REAL Black Wall Street Tour for $15 per person, or sign up for Tulsa Tours’ Art Deco and Greenwood Tour, a two-hour tour costing $50, which includes the history of Black Wall Street. The John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation also provides Greenwood tours. You can also virtually revisit Greenwood during its heyday through this innovative New York Times virtual re-creation of the neighborhood.

While strolling Greenwood, look down at the sidewalk for plaques memorializing Black-owned business destroyed in the massacre. They’re reminiscent of the “stumbling stones” found in Germany and around the world, that mark the homes of Holocaust victims.

Walking north, look for murals and street art on both sides of the Interstate underpass, and head toward Vernon AME church, which was built after the massacre. Then walk another block to the OSU-Tulsa campus, where you’ll find a graphic mural incorporated into the sign welcoming visitors to the university, which once was the heart of Black Wall Street.

Guidebook

Tulsa travel information

Dining

You’ll find several Black-owned restaurants on Greenwood Avenue, within a block of the museum, including Black Wall Street Liquid Lounge coffee shop; Wanda J’s Next Generation Southern food restaurant;

For an authentic taste of old-school Tulsa, try the historic Stutt’s House of Barbecue. Its still run by 80-year-old Almead Hill Stutts, who uses family recipes from her childhood in Mississippi.

For a taste of an Old West favorite, chicken-fried steak, try Tally’s Good Food Café on old Route 66.

You can find soul food in Tulsa at Evelyn’s, owned by the same woman who owns Wanda J’s in Greenwood. Open for breakfast and lunch Monday through Friday.

Taste Oklahoma’s take on Tex-Mex at El Rancho Grande.

Lodging

Fairfield Inn and Suites Downtown offers a tranquil setting just a few blocks from the Greenwood neighborhood.

The Ambassador Hotel Tulsa, Autograph Collection is a full-service business hotel that sometimes offers bargain rates on weekends.