Where a Hero Fell: Visiting the Medgar Evers Home in Jackson, Mississippi

The preserved home of civil rights leader Medgar Evers in Jackson, Mississippi looks like a modest mid-century ranch house, but it stands as one of Mississippi’s most haunting historical sites.

Now managed by the National Park Service, this turquoise residence tells the story of an ordinary family living under extraordinary—and deadly—circumstances during the height of the civil rights movement.

Visitors must literally step over the spot where Evers was assassinated in 1963 to enter the home, which remains furnished exactly as it was in the early 1960s. The monument also celebrates the continued activism of Evers’ widow, Myrlie.

This little-visited National Park Service site is considered so significant it’s included in the proposed UNESCO World Heritage Civil Rights Trail.

Table of Contents

The Night of the Assassination

On the night John F. Kennedy went on national television to discuss the nation’s struggle with civil rights, an assassin with a hunting rifle hid in a honeysuckle bush outside Medgar Evers’ home in Jackson, Mississippi.

When the NAACP leader arrived home later that June evening in 1963, shots rang out. Evers collapsed on the concrete floor of his carport as his family tried to save him. It was the first murder of a nationally significant civil rights leader, and helped lead to passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

A Home Preserved in Time

Today Evers’ suburban-style home in Jackson, Mississippi is preserved as a National Park Service site, and furnished as it was in the early 1960s. Visitors literally must step over the spot where Evers was shot to enter the home and learn about the martyred leader. Inside you can see bullet holes from the murder.

The home is both cheery and chilling, and a must-see.

The little-visited monument is one of the nation’s most important civil rights sites, and is even included as one of the 13 places to be included in the proposed UNESCO World Heritage Civil Rights Trail. A visit to the National Park Service-managed unit offers a sobering reminder look at the daily lives of civil right activists and their families. It’s also an inspiring tale about how Myrlie Evers, Medgar’s widow, continued his activism in the decades since the assassination.

The Evers’ turquoise ranch home looks homey and familiar. It’s not a rural farmhouse or shotgun shack, but a typical mid-century modern home, like the ones where many of our parents and grandparents lived. Today, walking through the paneled three-bedroom house, visitors feel at home. It has a large bath, central heat, attached storage room and a landscaped lawn. Located in what was the Elraine subdivision, it was just a few block from a white working class neighborhood.

The neighborhood was specifically developed for Black veterans who had government benefits that would help them buy a home. Life for the Evers children seemed idyllic, with plenty of kids in the neighborhood, and carpools to activities.

But Evers’ life outside home was hardly peaceful.

Medgar Evers: From Veteran to Activist

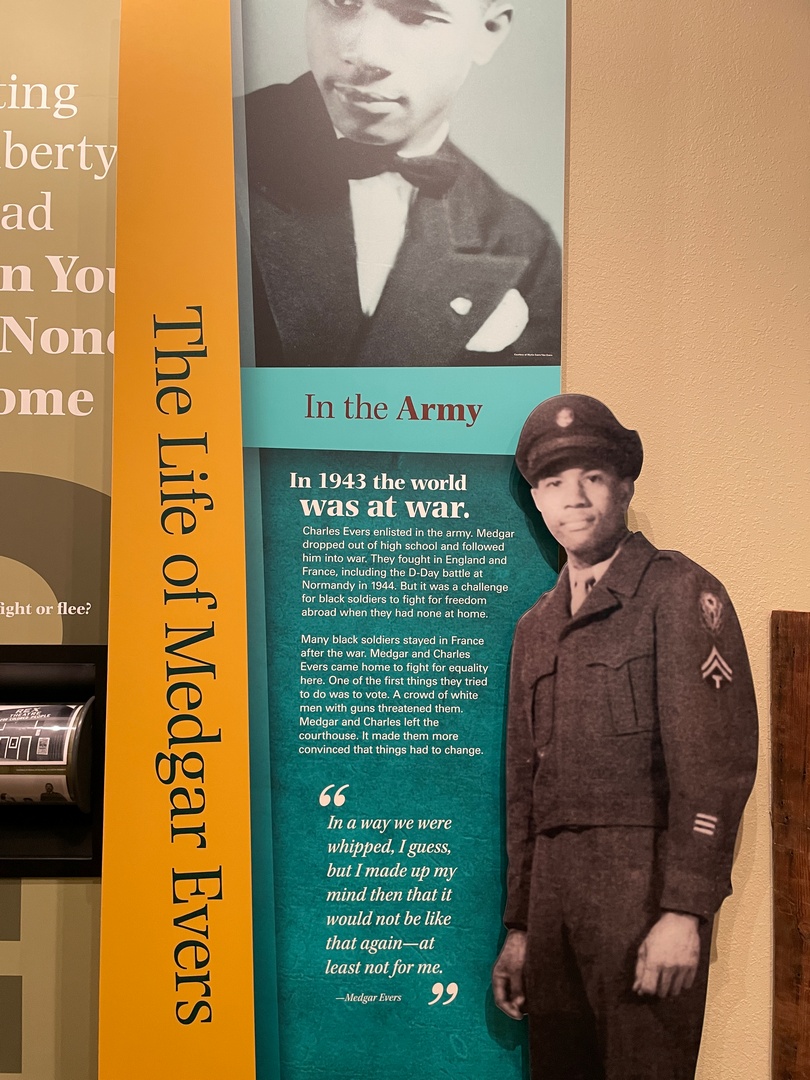

Evers, a Mississippi native, served in the U.S. Army during World War II, taking part in the Normandy invasion. When he returned to Mississippi, he and his brother were prevented from registering to vote in their hometown. Evers graduated from Alcorn State College, and tried unsuccessfully to enter law school at the University of Mississippi. (Later he would help James Meredith become the first Black student at the university, which set off riots.)

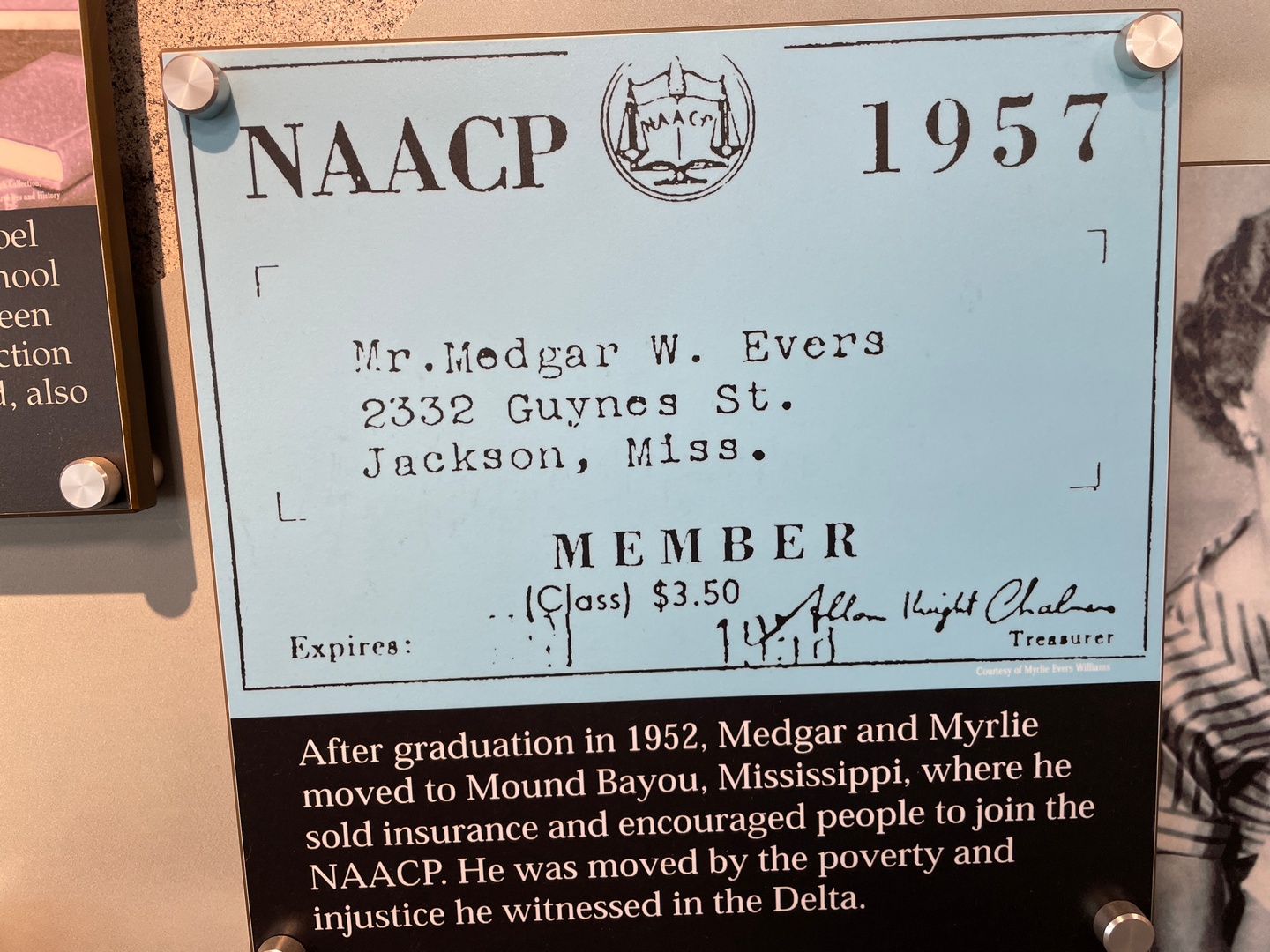

Evers worked as an insurance salesman traveling the state and was struck by the stark poverty he encountered, which inspired him to take a job as the first Mississippi field secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1955.

That role thrust him into the public eye. He became the voice and face of protests against discrimination in Jackson, the capital of one of the most segregated states in the country. He traveled across Mississippi to organize NAACP chapters, helped investigate the murder of Emmett Till, and brought national attention to the state’s widespread poverty and racial violence. This made him a target of White supremacists.

Living Under Constant Threat

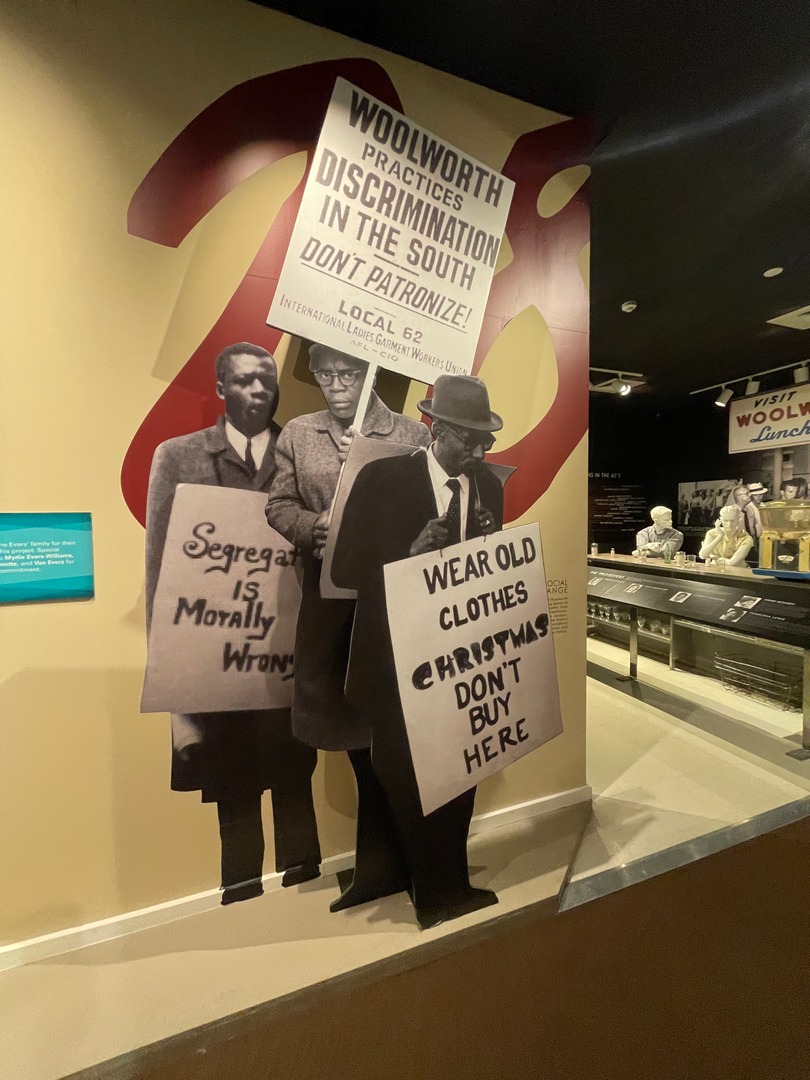

Before his murder he was punched in the face while riding a bus and was nearly run over by a car. Just a few weeks before his death, his home was firebombed after he organized a lunch counter sit-in in Jackson. His wife Myrlie put out the flames with a garden hose.

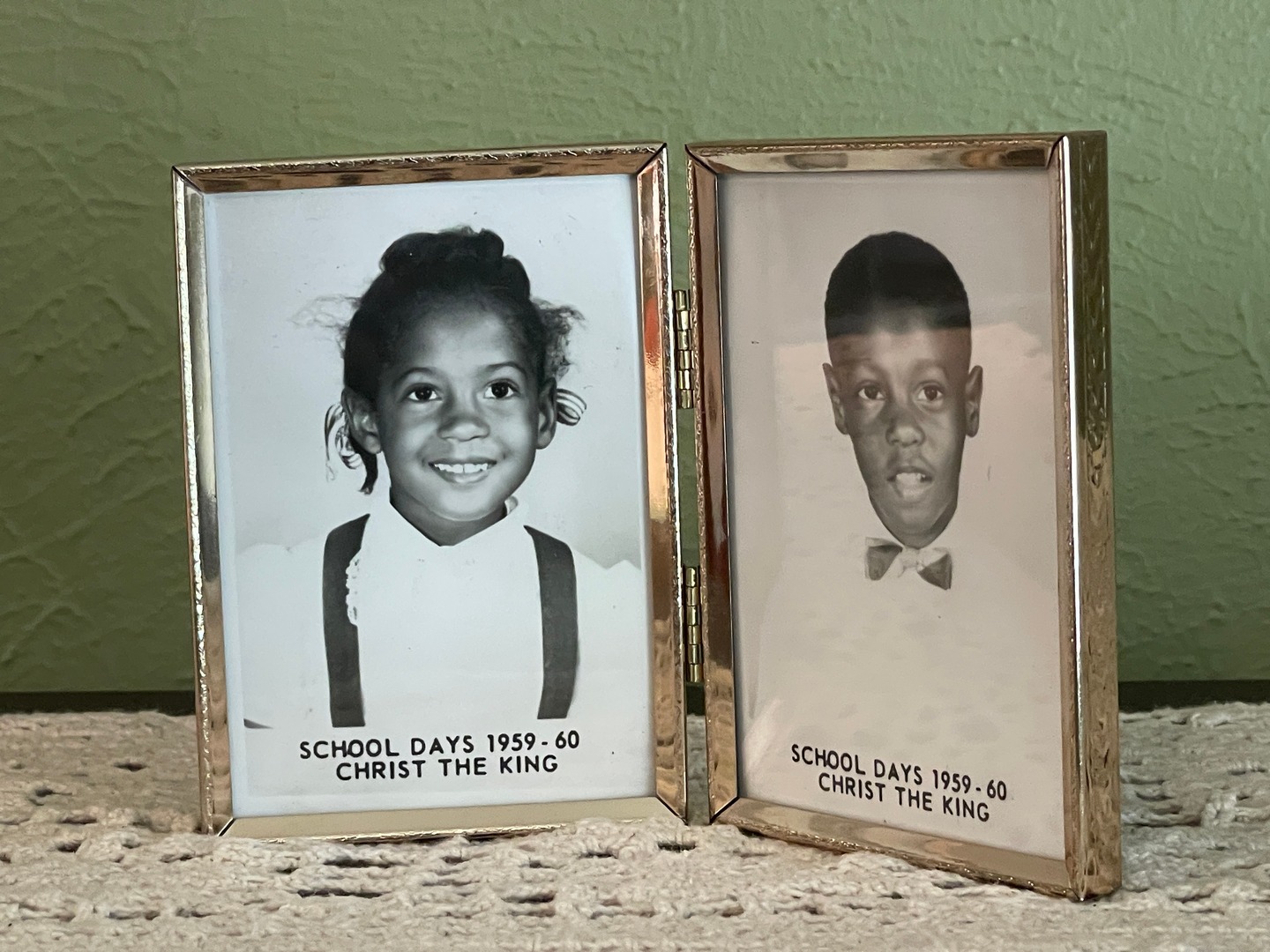

Indeed, the couple knew the danger they faced. For safety reasons, their home didn’t have a front door, but a side entrance from the carpool. The family positioned furniture away from windows, and the Evers children, Darrell, Reena and Van, didn’t have typical bedframes, but slept on mattresses placed on the floor to minimize the danger from an attack. The family regularly held safety drills, crawling to safety infantry-style to shelter in the tub in the bathroom.

But Evers still maintained a public profile, welcoming author James Baldwin at his home, along with James Meredith, who integrated Ole Miss.

The Assassination and Its Aftermath

On the night of his assassination, Evers was working at his office to organize a protest. He arrived home just after midnight, unloading T-shirts that read “Jim Crow Must Go.” As he entered his home, a shot rang out from a tangle of bushes across the street. Evers collapsed in the carport.

His wife and three children found him in a pool of blood. They rushed him to the Whites-only University Hospital in Jackson, where he was first turned away. When the hospital learned Evers’ identity, he was eventually admitted, but soon declared dead. His final words were: “Turn me loose.”

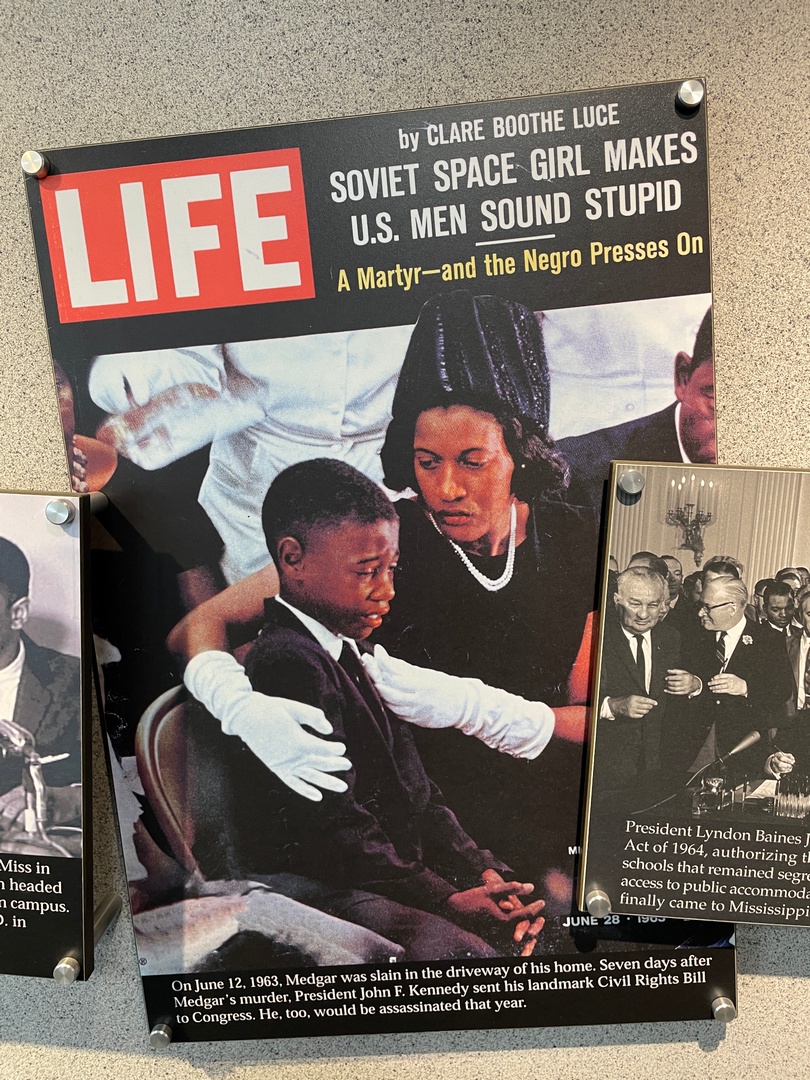

Evers’ funeral turned into a protest rally where hundreds were arrested. A funeral photo of Myrlie Evers consoling her son appeared on the cover of Life magazine. Evers, a veteran, was buried at Arlington National Cemetery, in Virginia.

It wasn’t hard to capture Evers’ assassin. Byron De La Beckwith, a member of the White Citizens’ Council, left his rifle at the scene. (It’s on display across town at the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum.) The weapon was covered with fingerprints, and De La Beckwith was quickly arrested. But justice was slow. Two all-White, all-male juries deadlocked, and Beckwith remained free for decades. Decades later, new evidence emerged, and he was finally sent to prison.

Back at the home, some visitors say it’s possible to see the bloodstain on the concrete floor, but on the day I visited, I wasn’t able to make it out. But you can feel Evers’ presence still. The house feels alive, and you can almost picture him stepping through the door at the end of the day.

The home is located northeast of downtown Jackson, at 2332 Margaret Walker Alexander Drive,

Jackson, MS, 39213, about a 15-minute drive from the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum. It’s open Tuesday to Saturday 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., and closed from noon to 1 for lunch. It’s closed on Sunday and Monday, but check ahead, hours can vary by season.

Remember the house is located in the middle of a residential neighborhood. If you can’t find a parking spot in front of the house, you can park at Myrlie’s Garden, which is located at the Missouri Street intersection. The garden itself is worth visiting for its historic markers and shade.

Other Evers Sites in Jackson

Along with the home, you can learn more about Evers at an extensive exhibit at the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, a must-see site for anyone on the Civil Rights Trail. But you’ll also find extensive information about Evers at the less well-known Smith Robertson Museum and Cultural Center, Jackson’s African-American history museum.

The building was the city’s first school for African-American children and the alma mater of the famed Richard Wright, author of Black Boy. The museum also has exhibits about the Woolworth’s counter sit-in by students from Jackson’s Tougaloo College, on the long fight against segregation, and the transatlantic slave trade’s link to Mississippi.

Surprisingly, you’ll also find an extensive Evers exhibits at Jackson’s airport, which is named for the activist. Jackson-Medgar Wiley Evers International Airport devotes an entire room before security to the civil rights icon. You’ll find videos, and artifacts, including a condolence letter sent by President Kennedy to Myrlie Evers.

The exhibit reminds me of Birmingham, where the airport is named for fiery civil rights leader Fred Shuttlesworth. While it’s only symbolic, it feels like a sign of progress to see two once-segregated transportation facilities named for powerful civil rights leaders.

To learn more about the era, watch President Kennedy’s full nationwide address here.